Featuring:

Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre - tenor saxophone, clarinet

Malachi Thompson - trumpet

Milton Suggs - electric bass

Alvin Fielder - drums

| 1. Unidentified Title I | 13:58 |

| 2. Unidentified Title II | 16:04 |

| 3. Unidentified Title III |

12:36 |

Bill Shoemaker - Point Of Departure

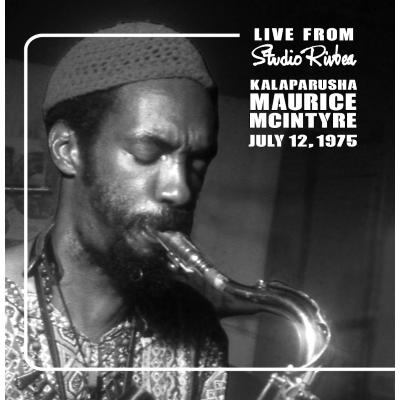

Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre’s is a perplexing, sad story. In the mid to late 1960s, he was in the thick of the teeming Chicago scene. Not only was he an early member of the AACM, playing in Muhal Richard Abrams’ Experimental Band and contributing to both the pianist’s Levels and Degrees of Light and Roscoe Mitchell’s Sound, he worked with everyone from George Freeman to J.B. Hutto and His Hawks. John Litweiler, McIntyre’s most tenacious advocate, led his notes to Humility in the Light of Creator, McIntyre’s stunning 1969 Delmark debut, by proclaiming him “a visionary of our times.”

McIntyre joined the AACM exodus to New York in the 1970s and thrived for several years. He taught at Creative Music Studio, where he recorded Kalaparusha with Karl Berger, Jack DeJohnette, and others for Denon. In 1975, he played on For Players Only, Leroy Jenkins’ ambitious large ensemble project issued by the JCOA. “Jays,” recorded with Chris White and Juma Santos (another CMS colleague), was the first track on the first of five volumes documenting the 1976 “Wildflowers” festival at Studio Rivbea. By the end of the decade, McIntyre was touring Europe at the helm of his own groups, recording notable albums like Peace and Blessings for Black Saint.

Yet, the bottom fell out on McIntyre in the 1980s. Drug addiction is the commonly cited culprit that saw him reduced to sustaining himself largely by playing on the streets; however, that does not fully explain why McIntyre was marginalized when his AACM contemporaries, in essence, were bankable. The short answer is that loft jazz had its moment, gigging at Rivbea and other grassroots venues was not economically sustainable, and, for whatever reason, Europe was not an option. By the time McIntyre assumed the mantle of the elder emerging from the wilderness at the turn of the century, he simply could not reassert his initial stature, despite solid recordings with The Light – Ravish Momin and Jesse Dulman – for Delmark and CIMP. He died in poverty in 2013.

Live from Studio Rivbea, July 12, 1975 makes a very persuasive case that McIntyre merits a place among prominent post-Coltrane tenor saxophonists, his searing lines, squalling vocalizations, and avant-gutbucket flourishes fitting in among Sam Rivers and Frank Lowe. McIntyre’s three untitled compositions on this date are sturdy, well-constructed blowing vehicles that withstood the terrific centrifugal force created by his quartet with trumpeter and AACM alum Malachi Thompson, Sound drummer Alvin Fielder, and electric bassist Milton Suggs. Suggs, who was also working with Elvin Jones at the time, is the real surprise, his propulsive facility matching Fielder’s, constantly pushing the music upstairs.

Why this band didn’t become a going concern adds to the mystery that is Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre. Their music had all of the components that made loft jazz so incandescent throughout much of the 1970s: passion, chops, and imaginative rewiring of the vernacular. McIntyre and Thompson were a formidable front line. Even though McIntyre is in excellent form throughout, Thompson’s solos are consistently riveting, a welcomed reminder of the trumpeter’s brilliance. While Live from Studio Rivbea, July 12, 1975 will undoubtedly be lost in the glut of overhyped Record Store Day extravaganzas and “complete” versions of previously available concerts or studio sessions, it meets the high standard of substantively filling in an incomplete picture of an intriguing artist’s work.

Pierre Crepon - New York City Jazz Record

If I wanted the world to recognize me, I had to come to a place that the world would come to. New York is the marketplace for any type of art,” Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre (who died eleven years ago this month at age 77) once told interviewer Fred Jung. “You come here if you have something to sell.” Born in Arkansas and affiliated with Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) since its 1965 inception, the product the tenor saxophonist had to offer was of the avant garde kind. It was not an easy sell in 1970s New York. The city had more of this kind of goods than its marketplaces could (or even cared to) absorb, a reality that led to the multiplication of alternative loft spaces. One of the most renowned of these spaces was saxophonist Sam Rivers’ Studio Rivbea, which was where this raw-sounding, previously unheard music was recorded in 1975. McIntyre, who was not a loft mainstay per se (even though he did appear on the first volume of the famed Wildflowers Sessions, recorded one year later, in 1976) was booked during a month-long summer festival that also featured saxophonists Byard Lancaster and Charles Tyler as well as vibraphonist-pianist Karl Berger and others. McIntyre’s music “was often confrontational and not at all conventionally attractive,” Ed Hazell writes in his informative liner notes. This is an interesting starting point for an examination of the music. Conventional conceptions of beauty were far from absent of free jazz, but there’s a gruffness to McIntyre’s playing that directs the music in an unknown direction: a rough, unstable edge that seems to be the center of gravity. He is joined by Malachi Thompson (trumpet), Alvin Fielder (drums) and Milton Suggs (electric bass), the latter whose contributions are certainly felt. The music combines moments of simultaneous soloing with traditional soloing patterns in an elastic mix that moves from sluggishness to urgency. The approach works well within the frameworks of the leader’s compositions, which include three unidentified originals that share somber shadings found elsewhere in the saxophonist’s work. Overall, the players do not come across as trying to make a grandiose statement. This recording seems to document the kind of music making made consistently engaging by the quality of its instrumentalists. And though NoBusiness has prolifically released unearthed music by Rivers, it’s an interesting choice by the label to inaugurate a series dedicated to a space (Rivers’ Studio Rivbea), rather than to a musician.

Fabricio Vieira - FreeForm / FreeJazz

Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre (1936-2013) veio de Chicago. Ligado à AACM desde seus primeiros tempos, participou de gravações seminais, como “Levels and Degrees of Light”, de Muhal Richard Abrams, e “Sound”, de Roscoe Mitchell. Em 1969, gravou seu álbum de estreia, o marcante Humility In The Light Of Creator. Na década seguinte, foi para Nova York, como muitos de seus parceiros de AACM, e por lá tocou sua carreira. Provavelmente a era loft foi a de mais intenso trabalho para ele. Mas poucos discos seus ficaram daquele período. Dessa forma, esse lançamento ajuda a preencher lacunas em sua trajetória, trazendo à tona um pouco mais de sua intensa música. Aqui vemos McIntyre, que toca sax tenor e clarinete, acompanhado de Malachi Thompson (trompete), Milton Suggs (baixo elétrico, que na época fazia parte da banda de Elvin Jones) e Alvin Fielder (bateria). São três extensas peças de nomes não identificados, que variam entre 13 e 16 minutos, captadas no Studio Rivbea em 12 de julho de 1975 – um ano antes de “Wildflowers”, do qual McIntyre participaria com um outro grupo. O núcleo dessa música são os diálogos entre sax e trompete – Thompson, morto em 2006, teve a carreira de maior destaque dentre os músicos desse quarteto, aparecendo em variados discos, circulando entre o pós-bop e o free. McIntyre, a partir da década de 1980, encontraria crescente dificuldade em fazer e registrar sua música, o que o levaria a tocar nas ruas e estações de metrô para sobreviver, morrendo na pobreza no Bronx, em 2013. Este quarteto, se tivesse ficado junto, poderia ter se sedimentado como um dos fortes sons da época.